(When Runner’s World cut me loose as a columnist in 2004, I

wasn’t ready to stop magazine work. This year I post the continuing columns

from Marathon & Beyond. Much of

that material now appears in the book Miles to Go.)

2004. We met in

person only once, and then for less than an hour a long time ago. Yet I count

Jack Foster as one of the greatest friends I’ve ever had. Like all the great

ones, he has never stopped giving.

Measured by the most said in the least words, one of the best books

ever written about running was really just booklet length – Foster’s Tale of the Ancient Marathoner. Its

first words, and far from its best, aren’t his but mine that introduce him to

readers.

“If a friendship can be measured by the number of letters two

people exchange,” I wrote in the Foreword, “then I can count Jack Foster among

my best friends. On my desk here now is an inch-thick folder of lightweight

blue aerogrammes postmarked ‘Rotorua, New Zealand.’ I feel I know Foster about

as well as I know any runner.”

At the time, we hadn’t yet met. We tried at the Munich Olympics,

before the marathon that he ran there at age 40. I wormed my way into Olympic

Village, found the New Zealand compound and knocked on the door that I’d

learned was his. No one answered.

Oh well, I thought at the time, I’ll try again later in the Games.

But a few days later everything changed for that Olympics and for all to

follow. No intruder sneaked into the Village again.

Our writing back and forth continued, peaking during his writing

of that wonderful little booklet (which I edited for publication in 1974). He

handwrote it in tiny script across almost 100 pages of aerogrammes.

By then the sport knew him as the world masters marathon

record-holder. His mark of 2:11:19, set at age 41 while silver-medaling at the

1974 Commonwealth Games, would stand until 1990.

We finally did meet, briefly, at the Boston Marathon in 1976. The

meeting began awkwardly, as we tried to reconcile the person imagined from

written words with the one now standing before us, speaking.

Though his measurements (about 5-feet-8 in height and weighing in

the 130s) were known to me, I was surprised by how small he looked. We expect

people who’ve done big things to be bigger than life.

Jack and I didn’t say much that night, at least not to each other.

We stood together at a question-and-answer clinic, where he wowed the crowd

with his simple wisdom. He did the same for me as he now gave voice to what

he’d told me by letter over the years. Though we never talked again, I would

never stop repeating his words.

Other runners feel that way too. Jack’s booklet was a treasure

when published 30 years ago and is much more so now. Originally priced at

$1.50, a copy sold recently on E-Bay for more than $100. I wouldn’t part with

my one tattered copy for 100 times more.

WHERE HE CAME FROM. Running humbled Jack at first, which might be why he retained

humility about his later successes in the sport. He remembered where he came

from, and knew that by stopping running he would soon return there.

His first sport was bicycling. After taking long, hard rides with

friends in his native England, Jack “drifted into racing” on the bike. This

continued through most of his 20s, until he settled into family and working

life in New Zealand. Biking only to work and back, and playing some soccer, he

imagined himself to be fairly fit at almost 33.

“Surely a half-hour run would be no trouble,” he said of his first

try. After going what seemed to be several miles, Jack arrived back where he’d

left his wife Belle.

“What’s wrong, have you forgotten something?” she asked. “You’ve

only been gone for seven minutes.”

Jack’s reaction: “Impossible. I was sure I’d run at least six or

seven miles. I was soaked in perspiration and felt tired. Now I was worried. If

I felt like this at 33, how would I be when I was 40?”

We now know that by 40 he was an Olympian, with his best marathon

time still to come. But he couldn’t have known that lay ahead when his began

running “only every second day, and I was working to maintain that 20-minute

jog even on alternate days. I kept at it.

"I liked the feeling after the run,

feeling the glow which comes after exercise. Sometimes the glow was a whole

fire, in fact a real burnt-out feeling!”

Running led to racing. “I noticed I was still very competitive,”

he wrote. “A hangover from my cycling days perhaps, or maybe my nature. My

competitiveness might better be described as a desire to excel, for I have no

‘killer instinct’ at all, no real will to ‘win at all costs.’ Getting my times

down was the motivation to do more and more running.”

Better times led to more training, to better times and... You now

know where the repeated cycles led.

Other runners have climbed as high, but none was a later starter.

Jack Foster wasn’t like the young superstars who seemed to drop in from another

planet, bringing with them apparent immunity to the limitations imposed on us

mere mortals. He was more like one of us, one who made very good.

He ran while raising four children and working fulltime. He knew

the feeling of starting to run as an adult, and of recovering from hard runs

slower than the kids of the sport did. And he wrote for us.

We lacked his late-blooming running talent. (His son Jackson,

himself a competitive bicyclist, called Jack “a white Kenyan – an

oxygen-processing unit on legs.”) But he spoke a language that any older,

part-time runner could understand.

WHAT HE TAUGHT. The highest form of flattery for a writer isn’t imitation. It’s

repetition – quoting the writer’s words as better than any you could make up –

or better yet, adopting his or her recommended practices as your own.

Jack Foster left me with three lasting lessons for enjoying a long

and happy running life. I’ve repeated them often in writing and speaking, and

practiced all three myself:

1. The

one-day-per-mile rule. Jack could race as hard and fast as runners

little more than half his age. He just couldn’t race that way as often as those

that much younger. Watch-time doesn’t necessarily slow with age, he said, but

recovery time usually does.

He outlined his recovery needs in the Ancient Marathoner booklet: “The after-effects [of a hard race]

vary, with me anyway. Sometimes I feel fully recovered in two or three days.

Other times I have a drained feeling for as long as three weeks.

“My method is roughly to have a day off racing for every mile I

raced. If I’ve run a hard 26-mile road race, then I don’t race hard again for

at least 26 days. I’ll go for daily runs okay but no really hard effort.”

One easy day per racing mile. That’s the Jack Foster Rule – my

term, not his.

2. Not

training. “A reporter once asked about the training I did,” wrote Jack. “I

told him I didn’t train. The word ‘training’ conjures up in my mind grinding

out 200- and 400-meter intervals. I refuse to do this.”

Nor did he run “the 150 miles a week that some of the top

marathoners are doing. I rarely did more than half that. I believe it is

possible to achieve results in a less soul-destroying way.”

He concluded, “I don’t train; never have. I don’t think of running

as ‘training.’ I just go out and run each day, and let the racing take care of

itself. It has to be a pleasure to go for a run, looked forward to while I’m at

work. Otherwise no dice. This fact, that I’m not prepared to let running be

anything but one of the pleasures of my life, is the reason I fail by just so

much.”

3. Timeless

racing. Jack added to the paragraph above that “failing” didn’t bother

him. Nor did “the prospect of running 2:30 or even 2:50 marathons in the

future.”

This would have almost unthinkably slow to him at the time he

penned this line, but “slow” is a relative term. Jack’s times would slip to

levels that were slow only to him – a 2:20 marathon at 50, and to six-minute

miles for 10K’s in his 60s.

He claimed not to let the old times haunt him. “The dropoff in

racing performances with age manifests itself only on timekeepers’ watches,” he

wrote. “The running action, the breathing and other experiences of racing all

feel the same. Only the watch shows otherwise.”

Jack chose to define a good race by the effort, not by the numbers

of a watch. He said, “All the other experiences of racing that attracted me

initially are the same as they have always been, and they still appeal to me.”

Later. Jack

Foster’s first sport, bicycling, and his last. He was struck and killed by a

car in 2004 while riding near his home in Rotorua, New Zealand – the same place

he’d started to run almost 40 years earlier. He was 72.

He wasn’t the first friend I’ve lost to a bike accident. It’s a

riskier sport than running. But Jack wouldn’t have wanted anyone to speak ill

now of his favorite sport, any more than Jim Fixx would have wanted to tarnish

running by dying of a heart attack on the run.

Jack went quickly, doing what he loved.

That’s not all bad.

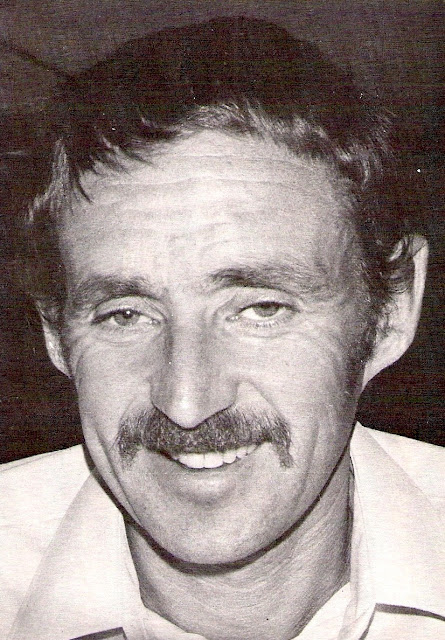

(Photo:

Jack Foster, the master of all masters marathoners.)

[Many books of mine, old

and recent, are now available in two different formats: in print and as ebooks

from Amazon.com. The titles: Going Far, Home Runs, Joe’s Team, Learning to

Walk, Long Run Solution, Long Slow Distance, Miles to Go, Pacesetters, Running

With Class, Run Right Now, Run Right Now Training Log, See How We Run, Starting

Lines, and This Runner’s World, plus Rich Englehart’s book about me, Slow Joe.]